Some of my fondest memories from early childhood occurred at the family computer in the basement, playing the history-based, kingdom-building strategy game, Age of Empires II. Since I wasn’t nearly as good at the “strategy” part of this game as my older brothers, I spent most of my time playing the Solo campaigns that centered around various historical figures, like Joan of Arc, Genghis Khan, etc. My absolute favorite of these was the William Wallace campaign, set right here in Scotland. While this was technically the tutorial campaign, I was so enamored with the thick Scottish accents and Wallace’s 5-and-a-half-foot-long Claymore, that I played it rather obsessively. I remember, vividly, the final chapter of the campaign–The Battle of Stirling–the drums beating and bagpipes playing victoriously in the background, as the narrator boldly announces:

“We have learned the ways of war. Now it is the English who will know fear.”

Epic.

Last Wednesday, I got stand on the very ground where Wallace struck the English down.

Epic.

The Wallace Monument is a large, spiraling tower, originally erected in the 19th century to memorialize the great Battle of Stirling Bridge. It stands on a hill, just minutes away from the University’s campus, surveying the Abbey Craig–a wide, green valley where the Scottish and English footsoldiers fought to the death.

After my morning class, I trekked up the hill to the monument–a gorgeous hike through some beautiful forests. After this, I walked up the 200+ narrow, spiraling steps to make it the top of the tower, where I was presented with a stunning view of Stirling’s entirety–a sprawling, magnificent town. The tower was so high in the hills, if I didn’t have my wind-worn, South-Dakotan legs, the winds would’ve swept me right off the top. They were harsh, yet invigorating, and the whole experience left me with great awe.

The tower is also home to several artifacts, including the deadly Claymore itself, which inspired some childlike giddiness in me. It’s incredible to be so close to physical, ancient history–a feeling I doubt I’ll ever get used to.

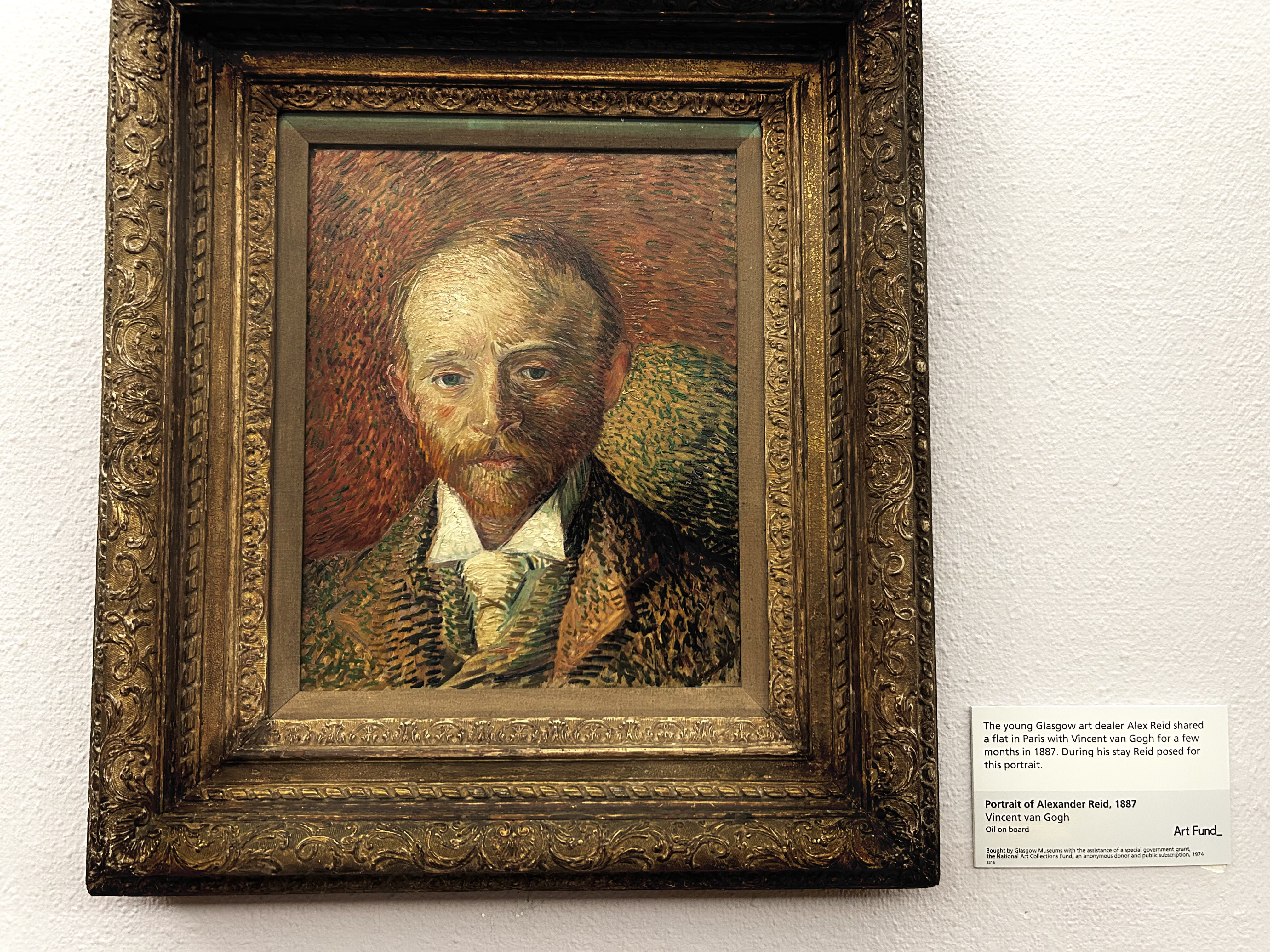

This weekend, I also had the opportunity to spend some time in Glasgow with the other WorldStrides Study abroad students. Those of us in Stirling took the early morning train and met up with the Glasgow students at the Kelvingrove–a massive and stunning art/national history museum in the center of the city. The Kelvingrove was home to all sorts of Scottish history and art, as well as a few pieces from some well-known names.

I could’ve easily spent several more hours there, but we had a full day planned ahead, and there were some Coos calling our name.

We took a bus to Pollok park, home to the grazing fields of some honest-to-goodness Highland cows. The gentle creatures were just as fluffy and adorable as one would dream of, and they seemed to understand their job well, coming right up to the fence and posing for pictures.

It was just like standing next to a Buffalo that wasn’t about to kill you.

Pollok park is also home to the magnificent Burrell Collection, a museum made up of Sir William and Lady Constance Burrell’s >8,000 piece, eclectic gallery. The Burrells were an extremely wealthy, art-enthusiastic couple who originally purchased the massive Hutton castle just outside of Glasgow to house their collection. Later in their lives, the couple decided to donate the collection to the public–the majority of it ending up just next to the park.

The collection was stunning. There were statues, paintings, stained glass, furniture, dishware, weaponry, and fashion pieces, ranging from 800 B.C, to the 1940s. The entire place was stunning, and a passionate love letter to the couple’s own appreciation for art and history. I can’t wait to spend another few hours there as soon as possible.

This weekend, I was also fortunate enough to experience my first Scottish national holiday, colloquially known as “Burns Night”. This holiday seeks to celebrate the life and works Scottish national poet, Robert Burns (most famous for writing Auld Lang Syne). Traditionally, this is done through an intimate Burns night supper with friends, featuring Haggis, Whiskey, and poetry recitation. To celebrate, I met up in the flat of some fellow study abroad students, where we watched a grim documentary about Burns’ playboy tendencies, had some real Scotch Whiskey, and tried Haggis pies for the first time.

It turns out, when there isn’t an American over your shoulder going on about how disgusting Haggis is, it’s actually pretty great. I found it delicious. And probably safer to consume than the average American hot dog. It tasted like Ground Beef+. 10/10, would eat again.

Overall, it was a lovely night of a few Americans pretending to be Scottish.

As fun and special as this week has been, I cannot lie that I’ve also felt an immense sense of melancholy throughout these new experiences as I keep up to date with the state of our country. My heart aches for everyone back home, especially in Minneapolis–perhaps my favorite city in all of America. Reading the news, watching the videos, and staying informed, all while outside of my home, has been a strange experience. When speaking to non-Americans, they tend to say things such as,

“Crazy what you guys are up to over there.”, or “You must be happy you escaped at just the right time.”

One person even said to me,

“You know your country is fucked, right?”

I know they mean no harm in saying such things, but these interactions have certainly spurred some complex feelings. I’ve been shocked to learn that my immediate reaction is to come to my country’s defense: It’s the powers of oppression, not the people. Or, There’s so much good to fight for there.

But there’s never enough time to delve into the complexities of America, its people, its government, and everything that makes it, simultaneously, undeniably Good, undeniably Evil, and absolutely worth fighting for. So for now, I’ve been responding to these interactions with some sort of apologetic, resigned answer.

In the midst of this turmoil, I was struck by some well-timed art and literature. In my Scottish history class, we were studying poetry surrounding the topic of liberation and freedom–both in the times of William Wallace’s rebellion and the 19th century boom in Scottish immigration to America. I stumbled upon this poem, titled “The Young Emigrant’s Farewell”, written by an unknown individual in Glasgow. It reads:

“Will you gang awa’ wi me, bonnie lassie, O,

Across the Atlantic sea, bonnie lassie, O;

I will take you to a land,

Where no tyrants do command,

If you’ll give to me your hand, bonnie lassie, O.

. . .

Let us drop this mournful tale, bonnie lassie, O,

And in some vessel sail, bonnie lassie, O;

To America we’ll go,

Far from scenes of want and woe,

Where our tears no more shall flow, bonnie lassie, O.

…

Now with you I’ll gang awa, bonnie laddie, O,

And leave my kindred a’, bonnie laddie, O;

Then through the world wide,

I will travel by your side,

And bid farewell to Clyde, bonnie laddie, O.”

Migration is a part of all of our histories. It is a part of our biology and human nature. To deny anyone this inalienable right is to deny the laws of nature. Therefore, it must be our duty to do everything in our power to protect this part of nature. I do not know what it will cost, but if the history in Scotland has taught me anything in the short time I’ve been here, it is that the will of the people has power to overthrow all forms of Tyranny, no matter how intimidating they may appear.

In his poem, “Robert Bruce’s March to Bannockburn”, Robert Burns writes:

“Wha for Scotland’s king and law

Freedom’s sword will strongly draw,

Freeman stand, or freeman fa’,

Let him follow me!

By oppression’s woes and pains!

By your sons in servile chains!

We will drain our dearest veins,

But they shall be free!

Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!—

Let us do or die!”

Leave a comment